It's such a charged term: middle class. Everyone has an idea of what it means, even if we don't agree on a single definition. But a median household is a decent place to start, as no matter what your definition of "middle class", I bet the median household fits within it.

So let's take a look at what that median household earns.

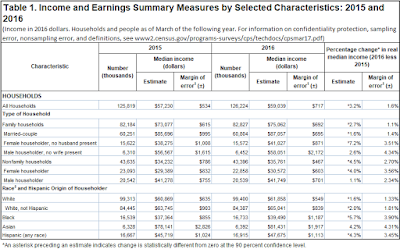

There's a lot of interesting data in the Census Bureau's report, but here is their high level summary broken down by household type and race (edited slightly for formatting). Note that only the percent increases noted with an asterisk are statistically significant, and all figures are noted in 2016 dollars.

|

| Link to Source Data, Census Bureau |

- The median household income rose 3.2% in 2016, up to $59,039. Buried within this average is an interesting wrinkle: the income of households with married couples only increased 1.6%, while households headed by women without husbands increased their income by 7.2%

- Black and Hispanic-origin households increased their income (5.7% and 4.3% respectively), more than Non-Hispanic white (which had a 2.0% increase) and Asian households (which did not change significantly).

- For the first time since 2007, the ratio of female-to-male earnings increased by 1.1%, to 0.805.

In each of these instances, we see a narrowing in income inequality. As Asian and White households are earning more than Black and Hispanic households, it's encouraging to me to see the latter two groups with greater increases in income, especially since all groups are raising their median income or holding steady.

A similar story is told with female householders with no husband present. (Dear God, they need a better term than that.) They are seeing the largest percent year-over-year increase of all the groups in this category at 7.2%.

These are really encouraging numbers. The median household in America is earning more overall, which is great. And a lot of groups that have historically earned less are seeing greater than average income gains, reducing the level of inequality.

But income inequality is still a damning issue. Even after these increases, the median African American household only earned $39,490, compared to $65,041 for Non-Hispanic White households, and $81,431 for Asian households.

While it's great to see the income gap between women and men closing, the size of the problem is still mind numbing. "Women with earnings" averaged $41,554, while men with earnings averaged five figures more, at $51,640.

Separate from issues of gender and ethnicity, in 2016 the top quintile of earners took home "over half of all overall income, a record". This is one of the discouraging areas in which we can see that inequality is increasing.

In fact, my somewhat rosy outlook looking at the Census Bureau's report is probably unwarranted. As the Washington Center for Economic Growth notes, comparing a median household of a group to its figures from a prior year can miss the bigger picture: namely, what is going on in groups who are far off from the median. Say, those in the top 5% of earners, or those in the bottom quintile.

|

So how do we reconcile these two narratives? I guess it depends on what we choose as a baseline.

Compared to the prior year, the median U.S. household got a healthy raise. But the middle quintile's share of the pie, how much of the overall income in the country that went to that 20% of households, shrank. And it's been shrinking since 1970.

This is where individual ideas about inequality tend to send us into debate. For many of us who are doing well financially, inequality might not be anything to worry about. If we're fighting over our share of the pie, it's not a big deal, because we're winning that fight. We have advantages, and maybe we work harder or are more gritty, or whatever. Still, we've been winning for a long while, and we'll probably continue to.

As a man, and an Asian, statistically speaking, I should not be surprised that our household earns more than average. According to the figures from the Census Bureau, that is to be expected.

But what if I weren't a man? What if I wasn't a mix of the two races that happen to earn the most on average? Would the issue of inequality matter to me more?

Maybe things are getting relatively better for the families right in the middle. And after all, there's nothing wrong with earning more income.

But no metric tells the whole story. Only one household can be the median, and the rest of us are all some distance away from that. If you're earning way less than the median, I suppose you don't care that much about how that one household is doing.

To the degree that we can see broad-based improvement in incomes, especially with those households who are making less, the closer those groups will be to the median, and the more representative that median will be.

Put another way, the more our society can help those earning less get towards the middle, the more that median income will really represent what the middle class earns.

As always, thanks for reading.

Want to read more? Here are our past posts on the American middle class:

Middle Class? How About Middle Quintile?

Middle Class Wealth

The Middle Class & Income by Location

The Unsustainable American Dream

Stagnant Wages, Inequality, and Early Retirement

*Photo is from emdot at Flickr Creative Commons.

Great information. Things are getting better. They are just not getting better for everyone at the same rate. I always find these reports interesting. In my industry, we are facing compression issues due to the increase in min wage.

ReplyDelete"Things are getting better. They are just not getting better for everyone at the same rate."

DeleteLeave it to the first commenter to summarize the findings better than I could. Thanks a lot, Dave. :)

I haven't tackled the minimum wage issue but that might be a good one for a future post. While my political bend tells me to support a $15 minimum wage, my inner economist knows that's not a great policy position.

"A similar story is told with female householders with no husband present. (Dear God, they need a better term than that.)"

ReplyDeleteAMEN.

I can guess that it was a man who thought up that term.

DeleteWhile we're at it, why are we still using "Hispanic"?

Terrible terminology aside, I do like the fact that government agencies are keeping track of this kind of granular data.

I read an interesting study that showed that wage inequality is decreasing (thanks primarily to wage increases at the bottom), but the top 20% (and especially the top 10% and top 1%) have seen their income and wealth rise as a result of "rising returns to capital".

ReplyDeleteOne way or another, I'm not too concerned with rising inequality of the top 1% because they are either super-mega-wealthy or super-duper-mega-wealthy and it makes little difference to me. (I should say, I don't like that some earn their wealth through cronyism or protectionism from the government, but the fact that they are wealthy doesn't bother me much).

On the other hand, I think that general poverty alleviation and "lifetime" social mobility (ie starting in the bottom 20% as a 20 year old and moving up to the middle by 50) matter quite a lot.

I saw some good evidence that we're doing well on the lifetime social mobility front both on average and at the bottom, except in cases where the working class becomes the non-working class (due to disability or a sudden lack of employment opportunities). On the other hand, we've not done so well with regards to poverty at least by a lot of figures.

In terms of what to do? I advocate that family, business and charitable organizations should pride themselves in giving the personalized help needed for someone to gain the skills and resources necessary to move out of poverty. The Federal/State government should not try to do that, but can consider transfer payments as a form of triage.

Hi Hannah!

DeleteRe: the very top earners, I agree that it's not necessarily a problem that they're wealthy. In fact, I think it's great. I do like to think about tax approaches and whether the way we tax for things (regressive taxes like sales tax, sin tax, etc) makes a lot of sense within the context of huge income and wealth inequality though.

Also agree on social mobility. Though I'd heard some different outcomes on how mobile a society America is these days. If you have a link to that study/article, please share it...would like to write about that potentially.

And agree on the role of families, business, & charitable orgs' role. Though I probably disagree on government's role: I do think our governments are foundational in addressing these issues of inequality and economic mobility, especially since so many of our public institutions (e.g. - public universities, or private universities funded with public grants/aid) are the primary drivers for reducing income inequality.

This is where I would start for the social mobility over a lifetime:

Deletehttps://www.ntanet.org/NTJ/66/4/ntj-v66n04p893-912-new-perpectives-income-mobility.pdf I saw another that used Social Security data that showed something similar though far less dramatic than the results claimed here. Also, be sure to remember that they aren't claiming social mobility within age cohorts, rather social mobility over time relative to the total population.

I'm not going to get into the sticky stuff. I'm pretty sure I've let you know I'm a big believer in income inequality and that the movement that denies it bothers me. Though the numbers in isolation are interesting--especially when juxtaposed with the bigger picture.

ReplyDeleteWhat's interesting to me--and, quite honestly, something that rings true--is the lack of a huge dip on the "poorest" 20% through the recession. I think the recession definitely had some long-term and horrific consequences for low-income families--the rental market and availability of affordable housing comes to mind first and foremost. But I remember income or job security not being the biggest concern. When your next job is going to pay barely above minimum wage anyways and you're not invested in the market... I wonder if the dip would appear proportionately larger if I zoomed in on that blue line around 2005-2010.

Hey there, Femme Frugality.

DeleteI was hoping you'd comment. Median income probably is not a great metric for measuring total inequality, but it is a heuristic for seeing how the middle group is doing (or, various groups in the middle).

That last chart is a tough one to figure, but it's only measuring the poorest 20%'s share of the pie. When you don't have much besides your income, and you have very little room to go 'down' to begin with, I think that may explain why there isn't as big of a dip in that period.

But it's just not going to show the pain that the poorest 20% felt, even if their small share of the pie remained static when the pie shrank.

Agreed all around! Median income is an imperfect tool, but I use it a lot myself. And it does provide some interesting things to think about when the micro and macro data morally conflict.

DeleteAnd exactly on the lower 20%. I remember hearing that from people while the madness was going on. Quite honestly, without a college degree at the time I didn't feel as horrifically impacted as the middle class. But I heard the same sentiment from other people, too. It's interesting to see the data presumably reflect those feelings as fact.

Interesting statistics! It's promising to see things getting better but as a society we still have lots of work to do.

ReplyDeleteAnd yes, completely agree that "female householders with no husband present" needs a better term. I mean, nobody says "male householders with no wife present." What's wrong with single female?

To be fair to the Census Bureau, they also do use the term "Male household, no wife present". So in their own whack way, they are being fair.

DeleteAnd the women saw bigger gains than the men. :)

Still, shitty term. I think they use that wording to mean something along the lines of "single mother", which they're using separately from just "single female" (that they'd put under "Non family households"). So much weird terminology...

We have way, way further to go. My pessimistic side says the groups at the bottom showed the biggest gains because they have nowhere to go but up.